Have you ever noticed something odd about The Lord’s Prayer? Like, it’s not the Lord’s prayer?

No, really. Check it out in Matthew 6 or Luke 11 (this week’s gospel reading) and you will notice a lot of things different from the versions we say in church. There’s that whole chunk at the end missing for starters. In a couple of places, the words we say differ markedly from what Jesus said, and some of them matter.

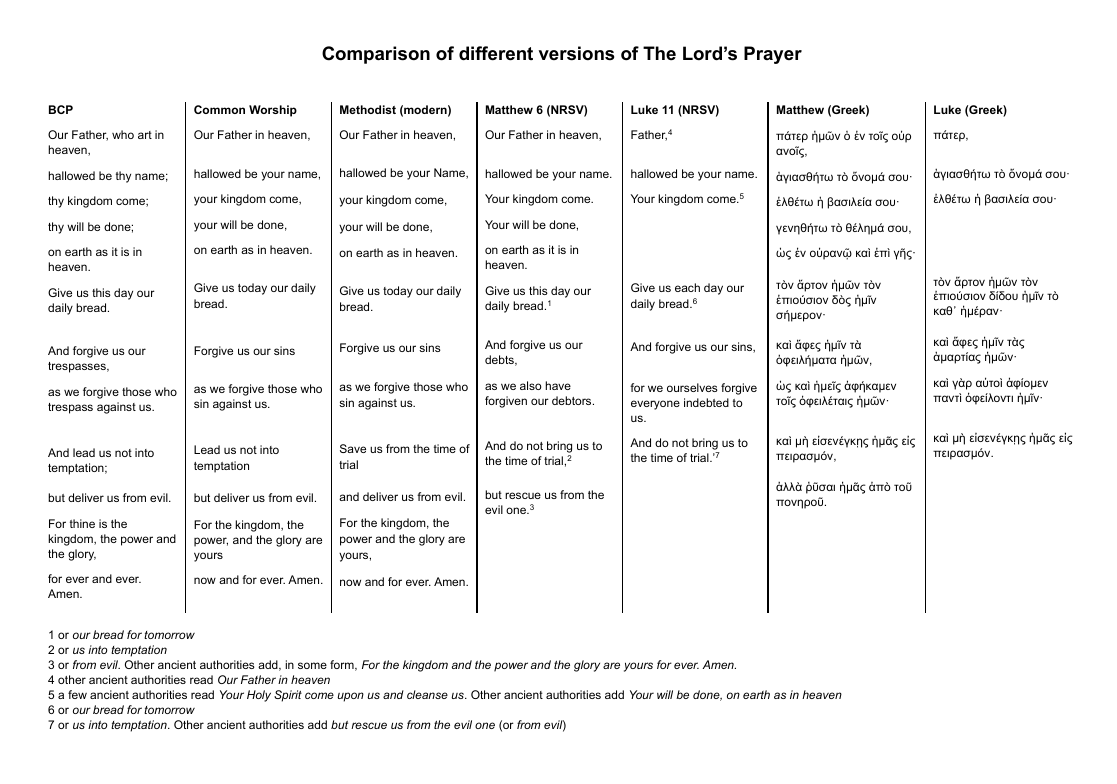

In this handy-dandy cheat-sheet [Lord’s Prayer comparison], I’ve set side-by-side the Anglican Book of Common Prayer (BCP, 1662) version, which is identical to the RC version except that the latter ends at ‘evil’, then two modern-language versions from Common Worship (CofE) and UK Methodism, then the texts from Matt 6 and from Luke 11, in English and then in Greek. For English, I’ve used the New Revised Standard Version, which corresponds closely with the Greek.

OK, let’s dive in.

Our Father in heaven: That’s Matthew, while Luke has simple Father. No problem.

hallowed be your name / your kingdom come / your will be done: Again, Matthew, while Luke has a cut-down version. Usually, we bracket the first of these onto ‘Our Father’ as if it’s part of the address, but check out the Greek (if you don’t read Greek, look for the ‘σου’ = your at the ends of the lines). You’ll see it’s poetic set of three. More like

make holy the name of you,

make come the kingdom of you,

make be done the will of you,

Incidentally, that last one is not a prayer that God would force me to obey him, nor even that people in general should follow God’s laws. It’s more like ‘just as your will is what happens in heaven, may it happen here on earth, too’.

on earth as in heaven: Matthew only. The Greek is beautifully poetic: as in heaven, so also upon earth.

Give us today our daily bread: Both English versions have notes on ‘daily’. The word only occurs here so it’s anyone’s guess what it might mean. (The culprit is ἐπιούσιον in case you’re interested.) In Basics of Biblical Greek, Mounce suggests ‘daily’, ‘sufficient for today’, ‘sufficient for tomorrow’, or ‘day by day’. But I don’t think there’s any significant difference, so ya pays yer money and ya takes yer choice.

Forgive us our sins: Matthew has ‘debts’, Luke has ‘sins’. Note that the word for debts (ὀφειλήματα) is soooo much bigger than paying back money. It includes aspects of wages (that which you are owed for your work), duty to a boss, obligation to an honoured person, and guilt as the moral debt incurred by sin.

Forgive us our sins: Matthew has ‘debts’, Luke has ‘sins’. Note that the word for debts (ὀφειλήματα) is soooo much bigger than paying back money. It includes aspects of wages (that which you are owed for your work), duty to a boss, obligation to an honoured person, and guilt as the moral debt incurred by sin.

Forgive, too, is bigger in Greek than in English. It includes wiping out or paying off a (monetary) debt, throwing something away or leaving it behind, as well as absolving one from the guilt of wrongdoing. In Jewish culture, all debts were cancelled/forgiven in the year of Jubilee. This is the concept we’re thinking here – the slate wiped clean, fresh start.

as we forgive those who sin against us: Matthew has, ‘just as we also have forgiven …’ while Luke has, ‘for we also forgive …’ One is a past deed that changes the present, one is a present continuous. It’s a done deed and it’s gonna keep getting done.

Lead us not into temptation: Ah. Now. This is where the poop hits the AC. While πειρασμόν can mean tempting to evil deeds, like the satan trying to make Jesus sin (Mk 1:13), or the teachers of the law trying to catch Jesus saying something wrong (Lk 10:25), I really don’t think this is the sense used here. Do we picture God gleefully trying to make us sin or hoping to catch us out with tricks and we must ask God if he would please stop being nasty? I trust that’s an immediate NOPE!

Trouble is, millions of people say this prayer every day, and some may get the impression that if we didn’t ask him nicely, God might tempt us into sin. The words we say, matter.

The other sense of πειρασμόν is testing or trial, like when you test how strong a girder is by loading it with weights. This is the sense we need here. We’re asking God to steer us clear of situations that we’d find hard to bear. It goes in a pair with the line after (common in Hebrew poetry): don’t bring us to [this bad thing], but rescue us from [that bad thing].

The Methodist version (save us from the time of trial) has this much better and I’m disappointed that Common Worship didn’t take the opportunity to correct this phrase that is, I fear, widely misunderstood.

Given that the words aren’t going to change any time soon, try changing the comma so that you get “lead us, not into temptation but deliver us …” It’s not quite right but it gives a better sense of asking God to lead us to good places and away from bad, rather begging a malevolent deity not to be nasty. ‘Cos God ain’t like that.

but deliver us from evil: Another bit of poor translation IMHO. It’s a hang-over from the KJV. Worth noting the the updated New King James has ‘But deliver us from the evil one‘, which is what Matthew actually said. It’s the ‘τοῦ πονηροῦ’ bit, literally ‘the evil’. Without the ‘the’ word it would be asking God to keep us away from evil in general – which would mean removing us from the world.

But Matthew said ‘the evil’ and, just like in English, when we use an adjective as a noun, we mean the person or thing with that trait. So The Good, the Bad and the Ugly refers to the good (people) the bad (people) and the ugly (people). Matthew’s prayer is better translated as ‘rescue us from the evil one’, and that’s very different from asking that we never encounter anything evil.

But Matthew said ‘the evil’ and, just like in English, when we use an adjective as a noun, we mean the person or thing with that trait. So The Good, the Bad and the Ugly refers to the good (people) the bad (people) and the ugly (people). Matthew’s prayer is better translated as ‘rescue us from the evil one’, and that’s very different from asking that we never encounter anything evil.

Again, I’m saddened that Common Worship didn’t take the opportunity to correct an old error. We’re not asking God to separate us from his beautiful but broken world. Rather, this the second half of ‘bring us not to the time of trial’ and has a similar meaning.

For the kingdom, the power, and the glory are yours now and for ever. Amen: Phew, back onto safer footing. While I’m normally a fan of contemporary language ‘cos Jesus spoke the common tongue to common people, I prefer the majestic BCP version with its sweeping crescendo to the towering heights of eternity. (Coo, weren’t that poetic!) Swap out ‘thine’ for ‘yours’ and you have

For yours is the kingdom

the power and the glory,

for ever and ever,

Amen.

However this ending is in neither Matthew nor Luke, and some folks do not say it. It’s a traditional closing called a doxology and was appended to Jesus’ words very early in the church’s history so, rather like the wet shirt scene in Pride and Prejudice, it’s not in the book but I’m happy to keep it.

However this ending is in neither Matthew nor Luke, and some folks do not say it. It’s a traditional closing called a doxology and was appended to Jesus’ words very early in the church’s history so, rather like the wet shirt scene in Pride and Prejudice, it’s not in the book but I’m happy to keep it.

There, I knew I’d get Colin Firth in somewhere.

Here are some resources on the Lord’s Prayer